Back to the Newsletter Contents and Home page

The Pine Marten in North-East Yorkshire?

by Michael Thompson

This article is reprinted with permission (with minor modifications)

from the North York Moors Association magazine “Voice of the Moors”

One of Britain’s most beautiful mammals, the pine marten,was relatively common in North Yorkshire until the

middle of the nineteenth century but this is not so today. In fact, they are probably extinct or, at least if present,

only as a remnant population. As they are predominantly nocturnal and secretive mammals, they are difficult

to sight or record.

One of Britain’s most beautiful mammals, the pine marten,was relatively common in North Yorkshire until the

middle of the nineteenth century but this is not so today. In fact, they are probably extinct or, at least if present,

only as a remnant population. As they are predominantly nocturnal and secretive mammals, they are difficult

to sight or record.

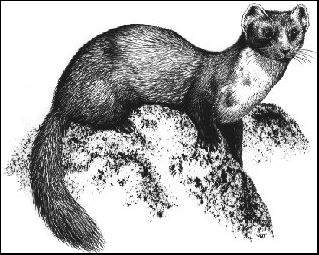

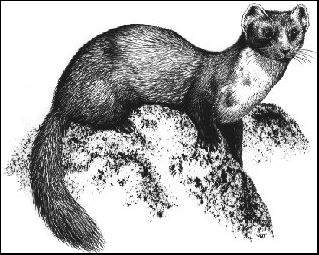

Pine martens are members of the weasel or mustelid family of mammals, and are one of our largest native

carnivores. Like the stoat, with its arched-backed gallop, the pine marten has a loping gait. About the size of a

domestic cat but larger than a mink, this mammal has a chestnut-brown fur or pelage, with a marked pale

yellow to orange throat patch and white belly. It has a large bushy tail. The mustelids have scent or musk

glands each side of the anus, hence the derivation of their name. Compared with other mustelids, the pine

marten has larger ears and a longer muzzle. In areas where it is common, it is sometimes seen crossing roads

at night in car headlights or hunting along hedgerows but the pine marten is also an excellent tree

climber.

Pine martens are for the most part a woodland species, using both conifer and deciduous habitats, especially if

they are associated with craggy rock cliffs. However, they will also be found in clear felled areas within forests,

pastures, scrub, coastal areas and treeless moorlands. With the expansion of Britain’s woodlands since the

mid-nineteen fifties, declining game-keeping activity along with protection in 1988 under the Countryside and

Wildlife Act 1981, the pine marten has increased in numbers and expanded its range. The female, on average,

has three kits per year in a den found in trees, between fallen rocks or burrows. Population density varies

according to available food supplies, with females and juveniles being most vulnerable. For much of their time,

these mammals lead solitary lives, with the males ranging over wide areas. Some individual male territories

are up to 40 square kilometres, with females’ up to 25 km.sq.: there is no overlap between same sex territories.

Basically, compared with other mustelids that have more young per litter, pine martens are slow breeders,

which means that there are few spare animals to re-colonise new or vacated areas. This leads to a slow

expansion of their range.

The pine martens’ main sources of food are mice and voles, but they will take other prey items such as small

birds, eggs and, in the autumn, berries. Although they are agile climbers, most hunting occurs at ground level.

Squirrels are another food source, as are game birds in unprotected pens. Extensive studies show that less than

1% of the diet of the pine marten comprises game birds.

It is still widespread and, in places, abundant in its northern and eastern European forest range. The pine

marten in Britain today, however, is confined to the Scottish Highlands, Dumfries, and with remnant

populations in the Lake District, Yorkshire and North Wales. The English and Welsh populations are small

and fragmented. This was not always so. There is archaeological evidence that pine martens were in Britain at

the end of the last Ice Age, thus, by definition, making them one of our native species. Here in Yorkshire,

skeletal remains nearly 10,000 years old were found at a hunter’s encampment at Star Carr, on the edge of the

Lake of Pickering.

Until the beginning of the nineteenth century pine martens were found throughout Britain but, quite quickly,

through constant persecution in the pursuit of game preservation, they disappeared from most of England.

During the Middle Ages, marten skins were much sought after as a luxury fur, as well as being hunted for food

to make up an exotic dish known as ‘marten’s pottage’. The Guild of Skinners in York would have worked on

marten pelts. Two leading Yorkshire naturalists of the late 19th century, William Clarke and William

Roebuck, writing on the status of pine marten in Yorkshire in 1881 stated, “Extremely scarce, and restricted to

one or two localities; formerly abundant and generally distributed. The decrease in its numbers appears to have

been comparatively rapid.” There is a scattering of sightings of the pine marten from north-east Yorkshire

from the mid 1850s onwards, with records from Whitby (1877), Kirbymoorside (1893), Swainby-in Cleveland

(1900), Levisham (1921), Everley near Hackness (1925), Stokesley (1970) and the mid-Esk (1973) area to

mention a few. A similar scattering of records are to be found in the natural history literature for the rest of

North Yorkshire, but with few, if any, in the last two decades of the twentieth century. However, records from

Colin Simms, Valerie Clinging and Derek Whiteley covering areas in the Yorkshire Pennines west of the

conurbations of Huddersfield and Wakefield indicated that, in the 1970s and early 1980s, there were small

populations of pine martens present in scattered woodland blocks.

Until the beginning of the nineteenth century pine martens were found throughout Britain but, quite quickly,

through constant persecution in the pursuit of game preservation, they disappeared from most of England.

During the Middle Ages, marten skins were much sought after as a luxury fur, as well as being hunted for food

to make up an exotic dish known as ‘marten’s pottage’. The Guild of Skinners in York would have worked on

marten pelts. Two leading Yorkshire naturalists of the late 19th century, William Clarke and William

Roebuck, writing on the status of pine marten in Yorkshire in 1881 stated, “Extremely scarce, and restricted to

one or two localities; formerly abundant and generally distributed. The decrease in its numbers appears to have

been comparatively rapid.” There is a scattering of sightings of the pine marten from north-east Yorkshire

from the mid 1850s onwards, with records from Whitby (1877), Kirbymoorside (1893), Swainby-in Cleveland

(1900), Levisham (1921), Everley near Hackness (1925), Stokesley (1970) and the mid-Esk (1973) area to

mention a few. A similar scattering of records are to be found in the natural history literature for the rest of

North Yorkshire, but with few, if any, in the last two decades of the twentieth century. However, records from

Colin Simms, Valerie Clinging and Derek Whiteley covering areas in the Yorkshire Pennines west of the

conurbations of Huddersfield and Wakefield indicated that, in the 1970s and early 1980s, there were small

populations of pine martens present in scattered woodland blocks.

Dr. Johnny Birks, secretary of the Vincent Wildlife Trust and an expert on the pine marten, has provided me

with a number of authentic pine marten records for north-east Yorkshire for the decade 1990 onwards. He

mentions pine martens recorded in coniferous woodland from Carlton Bank in 1995 and further east in 1998,

but on the same escarpment. In 1993, Charles Critchley, the Senior Ranger for Forestry Enterprise, unearthed

a skeleton of a pine marten, which had been buried by a gamekeeper, near Ingleby Greenhow. The animal in

question had been accidentally caught in a snare set for foxes. The last definite records of a pine marten from

this area are of one shot in 1983 near the Greenhow plantation, another killed on a road nearby in 1972 and a

sighting in 1996. The Ingleby Greenhow and Carlton records would seem to be within the National Park or

just outside it. Also, from within the Park, a record from Broxa in 1998. A well-authenticated record came

from Alne near Easingwold in October 2000, with two separae observers seeing the same mammal. According

to older records, a pine marten was seen near Huby, a neighbouring village, in 1973. Another pine marten was

seen near Dunnington in 1999. In all, Dr. Birks supplied me with 37 records from north-east Yorkshire but,

based on an analytical confidence scale, only seven would appear to be authentic. These records suggest that

the pine marten has never become extinct in north-east Yorkshire, and that a low density can sustain a viable

population.

These scattered records are important in assessing the future of this protected mammal. What can be done to

help its recovery in England and particularly in north-east Yorkshire, if recovery is what we want? For me, re-

establishing a native species within its proper habitat is a worthwhile exercise. But, in doing so, it is very

necessary to understand and, if possible, eliminate the factors that led to the decline in the first place. One

factor, and probably the most important, is attitudes. Unless people such as land managers, farmers,

gamekeepers, the shooting fraternity and environmentalists accept the idea of encouraging a major predator to

re-establish itself, then all would be worthless. This re-establishing can occur by natural spread but, as has

already been indicated, this is a slow process for the pine marten. A natural spread is occurring amongst

polecats, another large native mustelid, which has now reached Leicestershire from its Welsh-English border

strongholds, and it is breeding there. Interestingly, a polecat, and not a polecat-ferret, was killed on a road at

Marston Moor in Yorkshire this year. Although there is strong natural expansion of pine martens in the

Scottish Highlands, the possibility of them moving south through the Glasgow-Edinburgh conurbations seems

to me to be remote. The small fragmented populations in England are unlikely to expand, but just hold their

own. Thus, provided the habitat is right, a captive-release programme could be the answer, but there are other

serious questions to be answered before embarking on such a programme.

Talking to a farmer friend of mine, who is keen on wildlife conservation, I found considerable resistance to the

idea of reintroducing a major predator, on the grounds that it would upset the fine wildlife balance that is being

gradually being established in the countryside. Both foxes and pine martens, in some areas, compete for the

same food, and foxes are known to kill pine martens, but, according to the Scandinavian research, this has a

limited impact on pine marten numbers. However, would the introduced martens still have enough food to

sustain a viable population? Pine martens will always be thinly distributed, in the same way that rare birds are

distributed, so it is unlikely that they would encounter each other. There are more rare birds in the Scottish

Highlands, where the pine marten is well established, than there are in England. Here in North Yorkshire one

important major mustelid predator has been successfully reintroduced, namely the otter, on the Derwent system

of rivers. Captive-release prorammes have effectively reintroduced other native predators elsewhere in Britain,

by the R.S.P.B. and other statutory bodies, such as the red kite and the white-tailed eagle. The red kite

introduction programme at Harewood in West Yorkshire has, so far, been successful and I, along with others,

hope it won’t be too long before we will see red kites as a breeding species in North Yorkshire.

Other questions being asked by biologists and conservationists relate to various other factors, such as the

genetic pool. Would introducing new animals, with possible flawed genes, into an area where there is a small

remnant population affect that population? Would the resident pine martens drive out and possibly kill the

newcomers, for pine martens in their breeding season are highly territorial? When the conditions are not right

for an introduction programme, then is it morally defensible to do so?

The People’s Trust for Endangered Species and English Nature, along with Dr. Paul Bright of Royal Holloway

College, University of London, have surveyed six woodland regions in the south of England for suitable habitat

and polled local people about their attitudes to pine martens. An average 64% of farmers, 65% of gamekeepers

and 90% local residents said that they were in favour of reintroductions. A broader national consultation is

taking place and, if favourable, a programme will start in 2002. The North York Moors, with its extensive

forests, is not being considered as a suitable site for reintroductions, for there appears to be a remnant

population, which needs to be nurtured. Some of us would like to see the pine marten return to the North York

Moors but mostly by natural spread, although eventually by other means.

If any readers think they have seen a pine marten in north-east Yorkshire, please contact:

If any readers think they have seen a pine marten in north-east Yorkshire, please contact:

Dr. Johnny Birks, Secretary, Vincent Wildlife Trust,

3&4 Bronsil Courtyard, Eastnor,

Ledbury, Herefordshire HR8 1EP.

Telephone: 01531 636441. email: vwt@vwt.org.uk

(leave your name and telephone number, if Dr. Birks is out)

Michael Thompson 30.9.2001

Back to the Newsletter Contents and Home page

© Ryedale Natural History Society 2002.

Page last modified 21st July 2002. Site maintained by APL-385

One of Britain’s most beautiful mammals, the pine marten,was relatively common in North Yorkshire until the

middle of the nineteenth century but this is not so today. In fact, they are probably extinct or, at least if present,

only as a remnant population. As they are predominantly nocturnal and secretive mammals, they are difficult

to sight or record.

One of Britain’s most beautiful mammals, the pine marten,was relatively common in North Yorkshire until the

middle of the nineteenth century but this is not so today. In fact, they are probably extinct or, at least if present,

only as a remnant population. As they are predominantly nocturnal and secretive mammals, they are difficult

to sight or record.  Until the beginning of the nineteenth century pine martens were found throughout Britain but, quite quickly,

through constant persecution in the pursuit of game preservation, they disappeared from most of England.

During the Middle Ages, marten skins were much sought after as a luxury fur, as well as being hunted for food

to make up an exotic dish known as ‘marten’s pottage’. The Guild of Skinners in York would have worked on

marten pelts. Two leading Yorkshire naturalists of the late 19th century, William Clarke and William

Roebuck, writing on the status of pine marten in Yorkshire in 1881 stated, “Extremely scarce, and restricted to

one or two localities; formerly abundant and generally distributed. The decrease in its numbers appears to have

been comparatively rapid.” There is a scattering of sightings of the pine marten from north-east Yorkshire

from the mid 1850s onwards, with records from Whitby (1877), Kirbymoorside (1893), Swainby-in Cleveland

(1900), Levisham (1921), Everley near Hackness (1925), Stokesley (1970) and the mid-Esk (1973) area to

mention a few. A similar scattering of records are to be found in the natural history literature for the rest of

North Yorkshire, but with few, if any, in the last two decades of the twentieth century. However, records from

Colin Simms, Valerie Clinging and Derek Whiteley covering areas in the Yorkshire Pennines west of the

conurbations of Huddersfield and Wakefield indicated that, in the 1970s and early 1980s, there were small

populations of pine martens present in scattered woodland blocks.

Until the beginning of the nineteenth century pine martens were found throughout Britain but, quite quickly,

through constant persecution in the pursuit of game preservation, they disappeared from most of England.

During the Middle Ages, marten skins were much sought after as a luxury fur, as well as being hunted for food

to make up an exotic dish known as ‘marten’s pottage’. The Guild of Skinners in York would have worked on

marten pelts. Two leading Yorkshire naturalists of the late 19th century, William Clarke and William

Roebuck, writing on the status of pine marten in Yorkshire in 1881 stated, “Extremely scarce, and restricted to

one or two localities; formerly abundant and generally distributed. The decrease in its numbers appears to have

been comparatively rapid.” There is a scattering of sightings of the pine marten from north-east Yorkshire

from the mid 1850s onwards, with records from Whitby (1877), Kirbymoorside (1893), Swainby-in Cleveland

(1900), Levisham (1921), Everley near Hackness (1925), Stokesley (1970) and the mid-Esk (1973) area to

mention a few. A similar scattering of records are to be found in the natural history literature for the rest of

North Yorkshire, but with few, if any, in the last two decades of the twentieth century. However, records from

Colin Simms, Valerie Clinging and Derek Whiteley covering areas in the Yorkshire Pennines west of the

conurbations of Huddersfield and Wakefield indicated that, in the 1970s and early 1980s, there were small

populations of pine martens present in scattered woodland blocks.  If any readers think they have seen a pine marten in north-east Yorkshire, please contact:

If any readers think they have seen a pine marten in north-east Yorkshire, please contact: